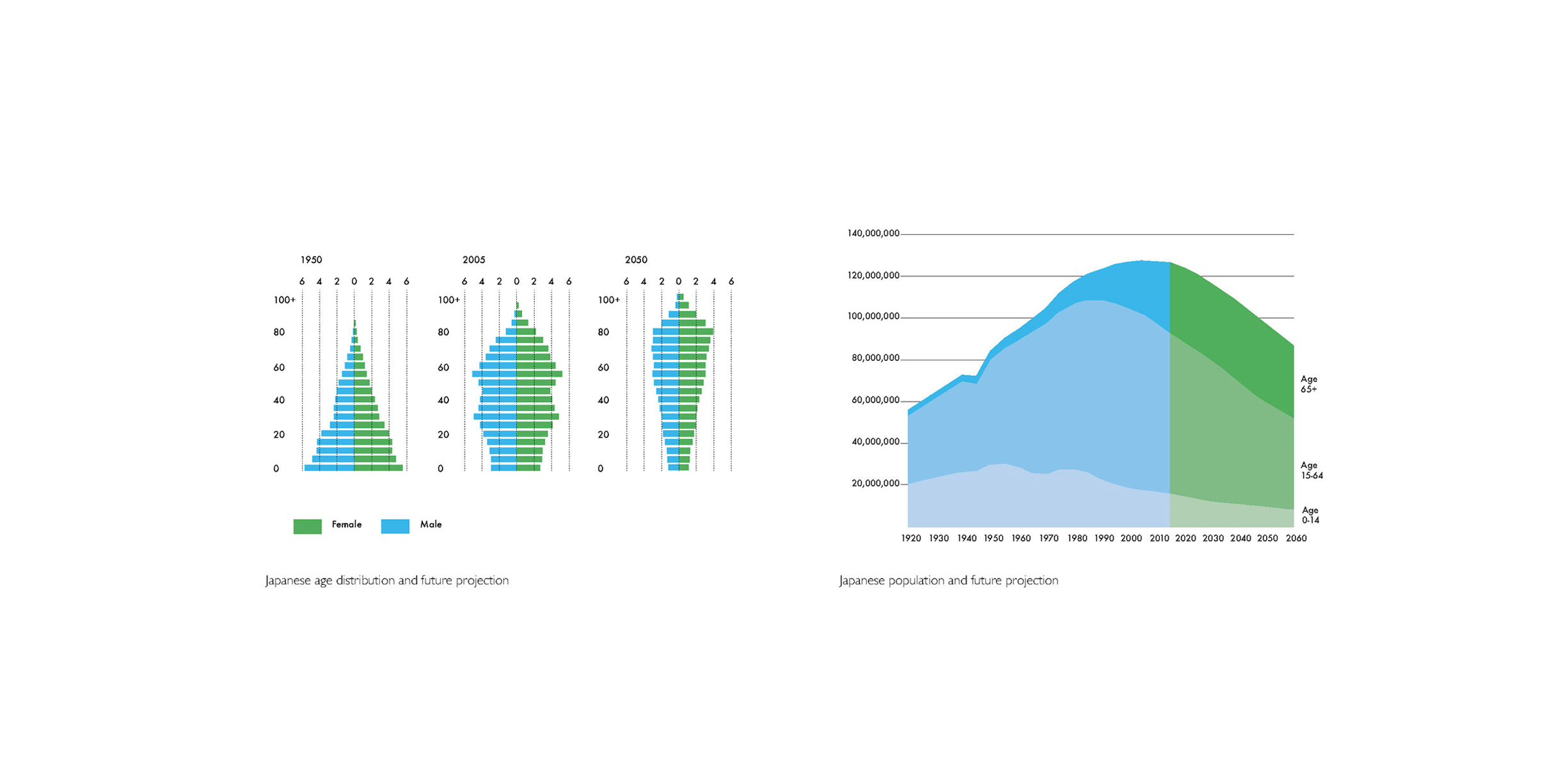

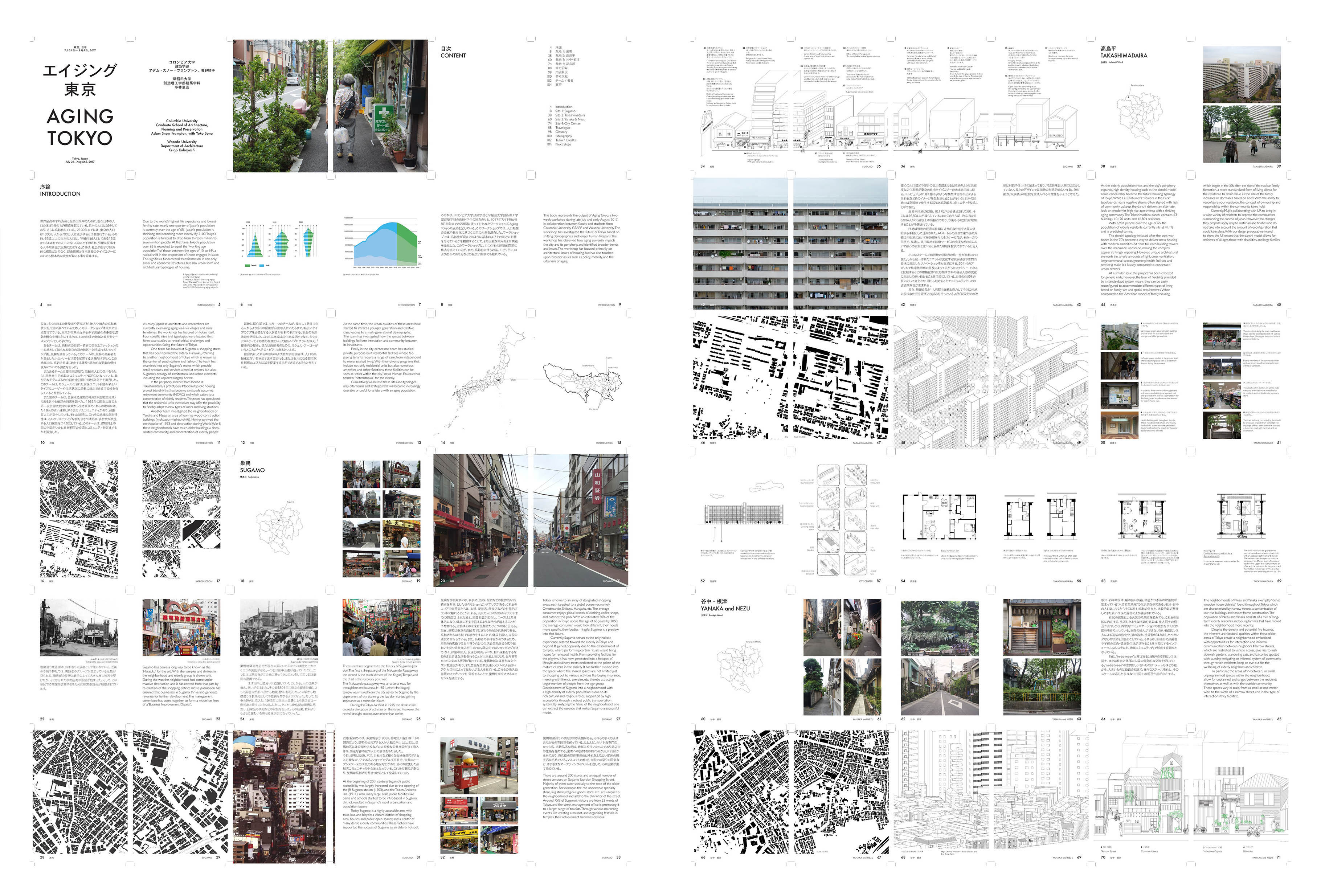

Due to the world’s highest life expectancy and lowest fertility rate, nearly one quarter of Japan’s population is currently over the age of 65. Japan’s population is shrinking and becoming more elderly. By 2100, Tokyo’s population is forecast to drop from thirteen million to seven million people. At that time, Tokyo’s population over 65 is expected to equal the “working age population” of those between the ages of 15 to 64, a radical shift in the proportion of those engaged in labor. This signifies a fundamental transformation in not only social and economic structures, but also urban form and architectural typologies of housing and public space.

During the summer of 2017, in collaboration with faculty and students from Waseda University, Aging Tokyo has investigated the future of Tokyo based on shifting demographics and longer human lifespans. The workshop has observed how aging currently impacts the city and its periphery, and located specific sites and case studies that reveal critical challenges facing the future of Tokyo. The study has focused primarily on new forms of housing instigated by aging, but has also touched upon broader issues such as social policy, mobility, leisure, and the urbanism of aging.

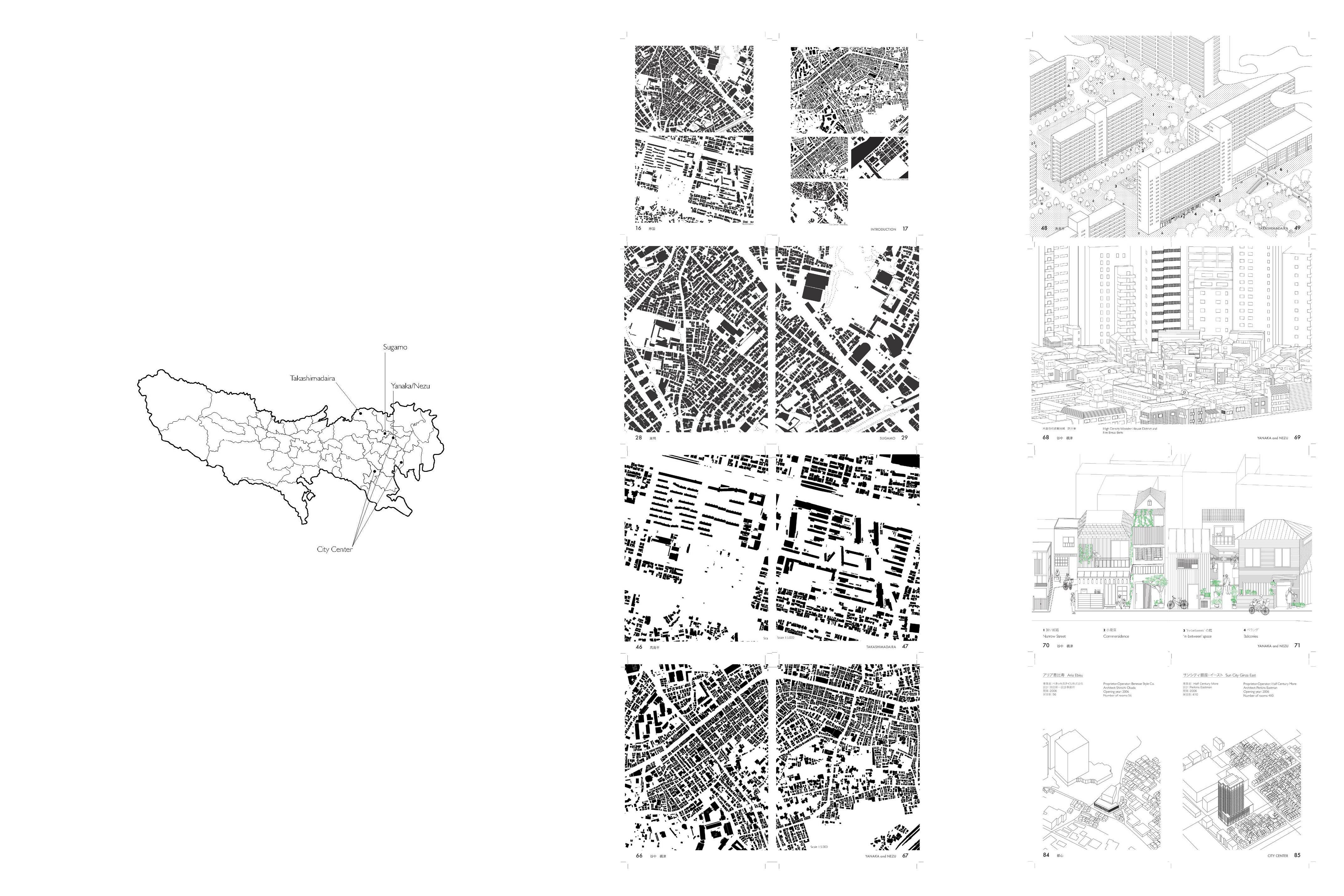

Four specific sites and typologies were located in Tokyo metropolitan area that form case studies to reveal critical challenges and opportunities facing the future of the city.

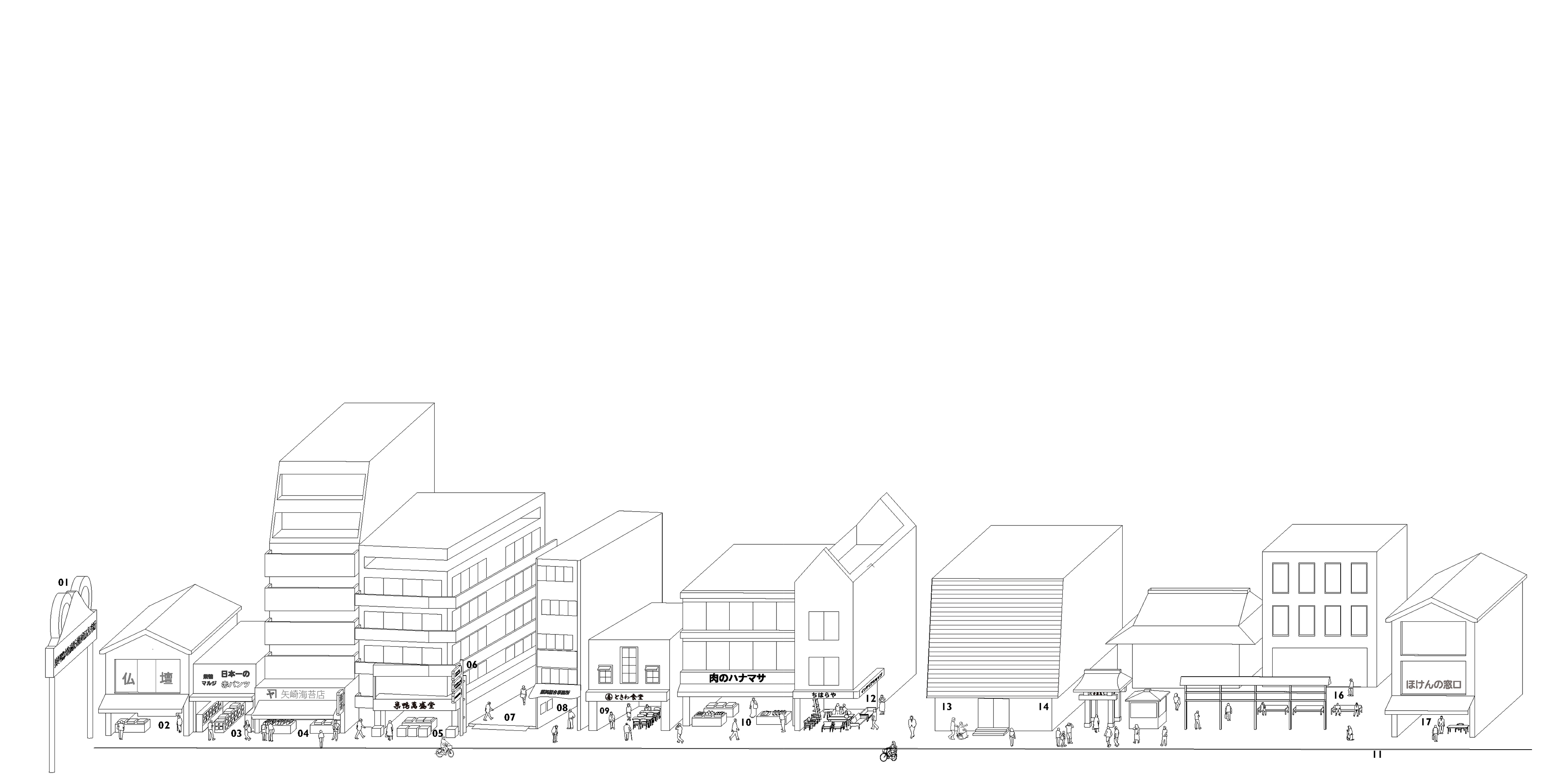

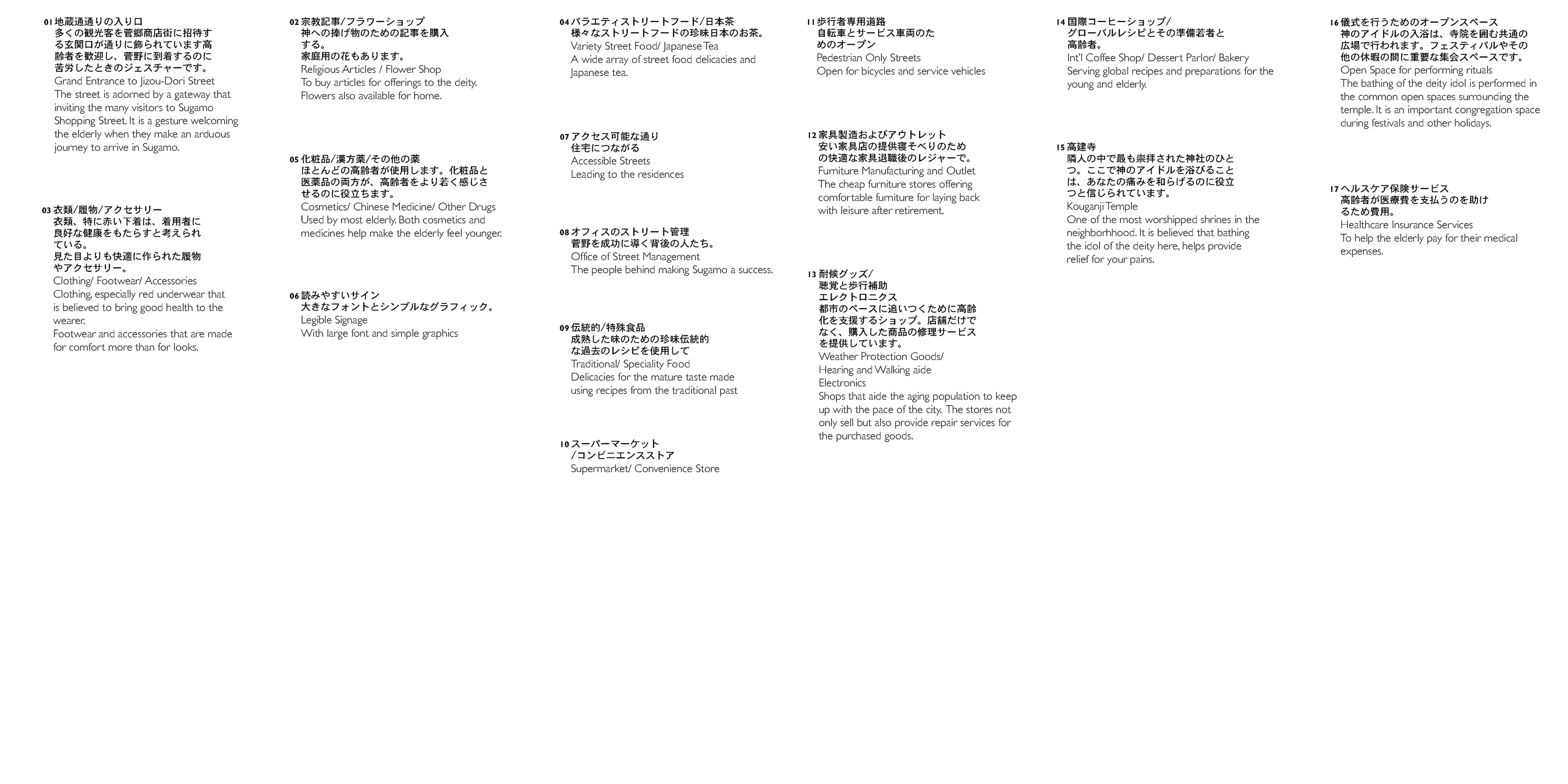

My team in this workshop has looked specificly at Sugamo, a shopping street that has been termed the elderly Harajuku, referring to another neighborhood of Tokyo which is known as the center of youth culture and fashion. We have examined not only Sugamo’s stores which provide retail products and services aimed at seniors, but also Sugamo’s ecology of architectural and urban elements, including the adjacent Koganji Shrine.

In the periphery, another team looked at Takashimadaira, a prototypical Modernist public housing project (danchi) that has become a naturally occurring retirement community (NORC) and which caters to a concentration of elderly residents. This team has speculated that the residential units themselves may offer the possibility to flexibly adapt to new types of users and living situations. Another team investigated the neighborhoods of Yanaka and Nezu, an area of low-rise wood-construction buildings (mokuzou-misshuu-chiiki). Having survived the earthquake of 1923 and destruction during World War II, these neighborhoods have much older buildings, a deep-rooted community, and concentration of elderly people. The last team has studied private, purpose-built residential facilities in the city center whose fee-paying tenants require a range of care, from independent to more assisted living. With their diverse programs that include not only residential units but also numerous amenities and other functions, these facilities can be seen as “cities within the city,” or, as Michael Foucault has termed, “heterotopias” for the elderly.

While our case study locations were considered as elderly neighborhoods, we have notice that at the same time, the urban qualities of these areas have started to attract a younger generation and creative class, leading to a multi-generational demographic. We have also investigated how the public spaces then facilitate interaction and community between its inhabitants. Cumulatively, we believe these sites and typologies may offer forms and strategies that will become increasingly desirable or useful for a future with an aging population.

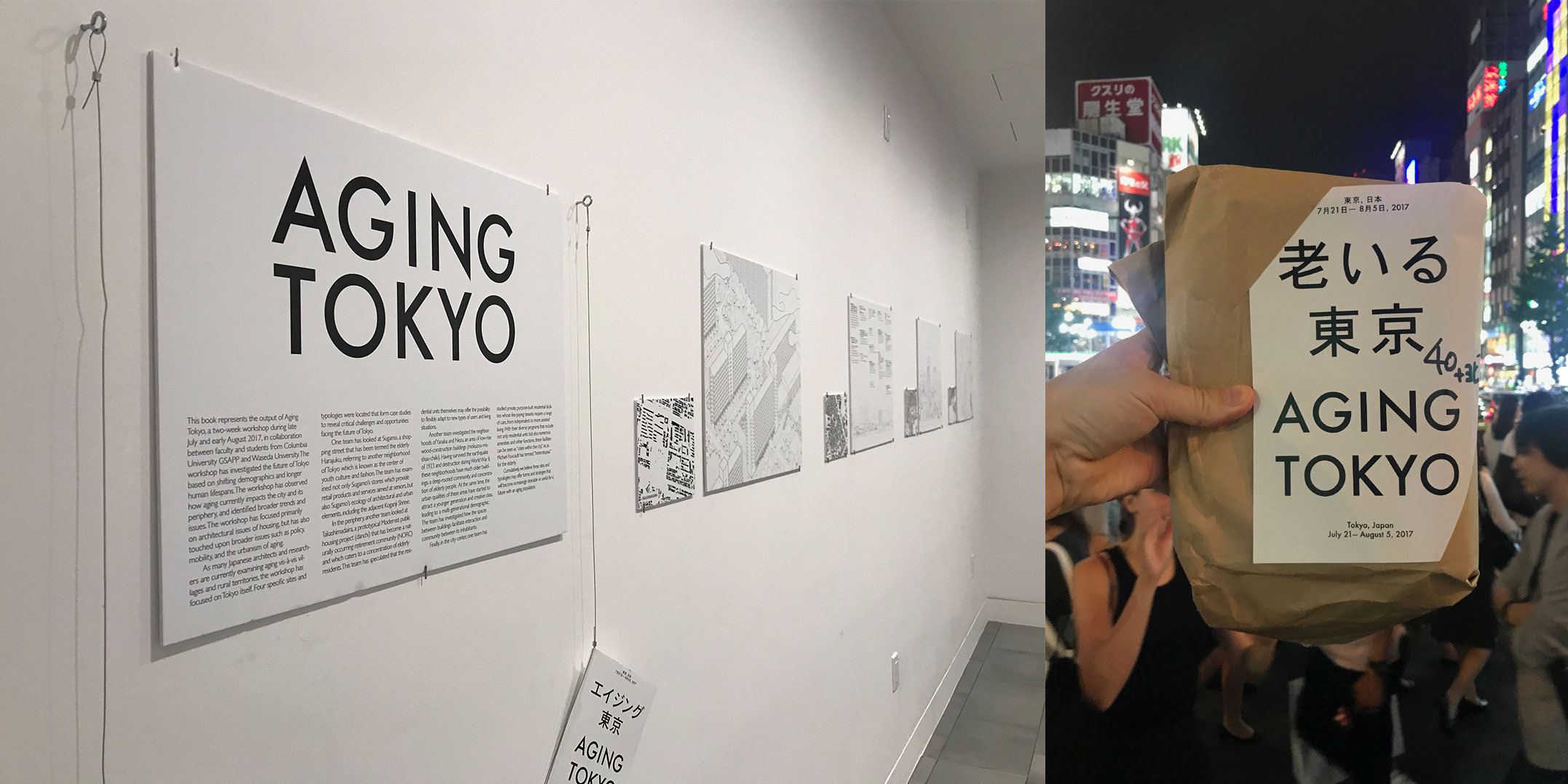

Exhibitions and presentations were held in Columbia University and Waseda University.